We are so accustomed to seeing the title 'Christ' following Jesus' name that it is easy to make the mistake of reading it as though it was his surname! Joseph and Mary Christ had a baby called Jesus...

Let's try and see it through fresh eyes.

In this formula the Father is God. Jesus by contrast is not God but the 'anointed one' instead. This describes his role.

Anointing entails 2 things:

a) empowerment- which God does not need, since he is already all powerful

and

b) commission- which God would not need because he is sovereign,

So the title Christ would not be fitting for Jesus, if he was God Almighty.

This juxtaposition of God and his Christ appears in many places. Perhaps one of the most significant is 2Co 13:14:

"The grace of the Lord Jesus Christ, and the love of God, and the communion of the Holy Spirit be with you all. Amen."

Ironically, this verse is often cited in support of the Trinity. Yet the word Father is nowhere in this verse! Instead we find Jesus distinguished here, once again, not only as someone other than the Father but also as someone other than the one God.

Have you checked out the main web-site at www.Godfellas.org ?

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

6 comments:

"Lord Jesus Christ" is a false term used by those who do not study and really know their Jewish savior.

Yeshua the Messiah is who I follow, and he worshiped Yahweh who is the Elohim.

Why bother with trivial elementary terms that do not promote the real Torah seeking Messiah who loved His Father and followed His Commandments? (Matthew 5:17-20)

John

John

In writing the New Testament documents the apostles were content to use, among others, the following Greek equivalents of Hebrew words:

iesous for y'shua,

chrestos for mashiach and

theos for elohim.

Surely these aren't 'false terms'. Neither, on that basis, is there any reason to assume that the anglicised equivalent 'Jesus' or the English title 'God' would be any less suitable.

The apostles even went so far as adopting the Jewish custom of replacing kurios for the divine name.

Personally, when reading the Bible aloud, I do choose to read out 'the LORD' as 'Yahweh'.

I also believe that, in view of the fact that translation can be the subtlest form of commentary, studying Hebrew and NT Greek can be of enormous benefit and should be encouraged.

However...

I think that accusing everyone who does not do this of 'not studying or knowing their Jewish saviour' is unnecessary and divisive.

Those of us who confess the one unipersonal God of Israel and his anointed Son should focus on working together to present this message to world and not allow ourselves to be sidetracked.

If we are to preach the truth, we should preach the whole truth, and not falling short of it in any way. If we know that "Jesus" is not the name of our "Messiah" then we should not preach that we follow a "Christ" which is NOT what he is. That is NOT the truth...

Otherwise, don't bother preaching the one God and his Son, if you are only doing half the job of the real truth.

Why hold up the truth because of feelings or concern for the other person's lack of knowledge? God will open their heart and mind if they are willing. IF not, they are not the elect...

Shalom

Theocrat,

I think you are wrong. You claim that the apostles wrote in Greek (a language that would be quite foreign to them. The canon we possess today is not what was originally written in those days. Scribal changes were made by Greeks. John would have simply said "We have found the Messiah" and would not have said "which is interpreted" (added later). This is a clear point in the matter. You should listen to some of Michael Rood's articles and videos if you are interested in learning some things about this.

Bob

I'm going to reply to these two messages in the order I received them...

First-

Shalom

I think this way of approaching the issue runs the risk of treating Jesus' name as though it were a sort of magic formula. As if it's power consists in the correct arrangement of vowels and syllables, as opposed to a person. Instead it is in identifying a particular individual that the purpose of a name lies. And in the case of Jesus the intended end result is to direct our faith towards him.

There were many Y'shuas and Y'hoshuas in 1st Century Palestine, so defining the correctness of the name in the narrow sense you propose cannot be the decisive issue. Surely that which distinguishes the Y'shua who is the anointed one, apart from all the others, is what the scriptures tell us about him. What he taught and what he did- these tell us what his name means.

This would be most consistent with the wider usage of the word 'name' throughout the Bible, according to which it comes to mean the summation of an individual's character and reputation (to have a good name or a bad name)- all that they are. Their entire persona comprised in a word.

Therefore it is an understanding of the person, message and work of Jesus that constitutes the true knowledge of his name.

So, when we read in Acts 8.12 that Philip preached the kingdom of God and the name of Jesus Christ this doesn't mean that he was just teaching the people how to pronounce it correctly.

In John 17.6 Jesus states that he has manifested God's name to the disciples. Yet there is no mention of Jesus ever pronouncing the name of Yahweh in any of his discussions with them in any of the gospels. What he did do was reveal the Father's character in action and give them his words.

Exodus 34.1-7 also goes beyond the narrow definition of name. In it God proclaims his name before Moses. But Moses already knew the name Yahweh, at least as far back as Exodus 6.3. What God does in these verses, once more, is declare his character as well.

I repeat my original statement. If the New Testament itself calls 'y'shua hamashiach' by the equivalent Greek term 'iesou christou' I don't see why we shouldn't do the same and call him, in accordance with our language, Jesus the Christ.

I have no issue with someone having a preference for 'y'shua' over 'Jesus'. We're all calling on the same person here and we have so much in common, it seems. I do hope that you will come to accept this.

Bob

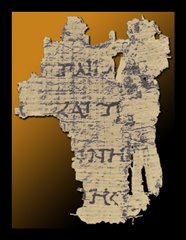

Where is the evidence of these scribal changes? We have extant manuscripts which date all the way back to within the lifetime of the apostles -7Q5 (pre 68 AD), the Magdalen Papyrus (c.66 AD) and P52 (c.120)- and all of them are written in Greek.

There is also ample evidence within the New Testament that Jesus spoke Greek, including some passages which would not make sense unless he did.*

By the time of Jesus the Greek language had been the lingua franca of the whole Eastern mediterranean world for centuries- since the conquest of the region by Alexander the Great.

Archeological discoveries in Palestine, including Galilee, such as coins, documents, popular plays and inscriptions bear this out and show that the vast majority of Jesus' Jewish contemporaries would have had a very good command of Aramaic, Hebrew and Greek.**

In order to establish what you propose this enormous burden of proof would have to be shifted first. What do you have to offer that is of sufficient substance to do this?

I'm also concerned about the implication in what you say that our New Testament is in some way different from the one written by the apostles. I suppose I am proceeding on the basis that New Testament faith presupposes a faith in the New Testament- the validity of the documents. If, according to you, they aren't entirely reliable due to scribal alteration, I wonder what your faith is based upon. Doesn't this mistrust of the gospels leave us with nothing to go on but conjecture?

For now I am content to put my trust in the Greek New Testament documents which God in his providence has seen fit to preserve and not cast doubt upon them on account of something a text, which in all likelihood has never existed, might have said.

Your reference to John's (Shouldn't it be yochanan?) offering of an interpretation to the Hebrew designation Messiah for the benefit of his Greek readers is apt. It should serve as an example to us. Obviously his concern was to present Jesus in a way that was intelligible and relevant to his Gentile readers. So he was careful to use a Greek term equivalent to the Hebrew one to ensure that his message would have currency in the broadest possible circles. For him it wasn't a matter of the kind of either/or choice you are insisting on.

In contrast you are citicising me for attempting to follow John's example by describing Jesus in a way most congruent to modern English speakers. In London today if you speak of Jesus the Christ people immediately know you mean the Jew from Nazareth described in the Bible, which is exactly what I'm trying to convey, therefore the name is perfectly adequate in doing what it is supposed to do.

*

Mark 7.24-30: the Syro-Phoenecian woman is unlikely to have spoken Hebrew. More importantly, 7.26 (he de gyne en Hellenis) shows the woman to have been Greek speaking.

Mark 12.13-17: this debate hinges on the inscription on the coin. Some have been discovered and they are in Greek. Between 37 BC and AD 67 no coins with Aramaic inscriptions were allowed in Palestine.

Jesus spoke to Pontius Pilate whose languages would have been Latin and Greek.

John 21.15-17: Jesus' conversation with Peter recorded here relies on shades of meaning in the Greek words which do not exist in Hebrew or Aramaic.

**

Sepphoris, the capital of Galilee only 6 kilometres from Nazareth had a theatre capable of seating 5,000 where plays were performed in Greek.

Jesus' words to Paul about kicking against the pricks were quotations from the Oresteian trilogy by Aeschylus. Even one of Jesus' trademark expressions 'hypocritai' (hypocrites) is not in evidence in a figurative sense anywhere prior to him and seeems to have been borrowed from the realm of Greek theatre.

Galilee itself is full of Greek inscriptions dating from Jesus' time showing that even orthodox Jews had a good command of the language, using it in both the synagogues and on their tombstones. One notable example is the 'Stone of Forbidding' in the Jerusalem temple, which was written in Greek script.

Post a Comment