It seems to me that when Jesus referred to himself as possessing ‘divinity’ it was invariably in terms of the indwelling Father, not the incarnate ‘God the Son’. He never speaks of ‘the Son that dwells in me’. Instead, Jesus was indwelt by his God in the same way the ark of the covenant was. In John 17:3, Jesus clearly sets himself in contrast to ‘the only one who is truly God’, the Father (see also John 5:44).

Furthermore, where the title ‘god’ is applied to Jesus by others, it harmonises far better with the Hebrew Bible to read it in terms of a functional equality, as opposed to an identity of substance. Moses was made a god to Pharaoh (Exodus 7:1) because he acted as Yahweh’s stand-in for his dealings with Egypt. In the same way, Paul describer the Satan as ‘the god of this age’ in that he occupies the dominion, usurped from Adam, that the Son will enjoy in the age to come. At any rate, this certainly seems to be the sense in which Jesus understood himself to be ‘god’ since, in John 10:34-36 it is Psalm 82 and not Deuteronomy 6:4 that he chooses to cite by way of explanation.

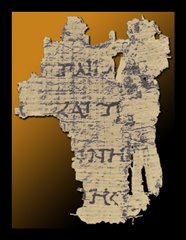

Of course, the distinction between ‘small-g’ and ‘big-G’ in our English translations is arbitrary, since there was none in the original Hebrew or Greek manuscripts.

Jesus functions as God towards humanity in that he did and spoke of himself as doing things which up to that point only God was thought of as doing (the general resurrection and judgment, the forgiveness of sin etc.)

Yet for all this, I would insist that there is no evidence that the apostles ever deviated form the strict unitary monotheism of the Jewish forefathers. There is still only one Creator God, the Father, in spite of the addition of a vice-regent, Jesus. Surely it is significant that the only clearly articulated ‘incarnation’ theology in the New Testament is found in the mouths of mistaken pagans (Acts 14:11). According to 1Tim 2:5, God is one and his Son is a man (wouldn’t this have been the perfect place to introduce the ‘god-man’?).

Holding the concept of Jesus being ‘god’ in a ‘homoussian’ sense (being of the same substance as God the Father- a Greek term not found anywhere in the Bible, but introduced during the patristic period to articulate the relationship between persons in the Trinity) has a double effect:

Firstly it divides the godhead, violating what according to Jesus was the first and greatest commandment (Mark 12:29-30- this is where Jesus does choose to quote Deuteronomy 6:4!). This is borne out in the contradictory Athanasian creed that ‘the Father is God, the Son is God and the Spirit is God, yet there are not three Gods, but one’.

Secondly, it eclipses Jesus’ humanity- an aspect upon which the most heavy scriptural emphasis is laid. Evidence of this is found in the Chalcedonian declaration that the Son possessed an ‘impersonal’ human nature. Hence he is ‘man’, but not ‘a man’. Read in the light of 1 John 4:3 this statement should cause alarm bells to ring.

What about the holy spirit?

In the development of patristic thought, the spirit didn’t become a person in the godhead until long after the Son. Strictly speaking, the spirit of God would appear to be his operational presence, as opposed to another person in the godhead. It is God’s dynamic, reaching into the world to create, inspire, work miracles etc.

Furthermore, it would seem to connote the ‘inner life’ of God, often being used synonymously with his thought and by extension, his expressed word. Of course, the same could be said of our human spirits. They too can be vexed, grieved etc. without being another person ‘subsisting’ within our ‘essence’.

It may even be that ‘spirit’ is not an ontological category at all but instead, a metaphor. The literal meaning of the words ruach in Hebrew and pneuma in Greek are in both cases ‘wind/breath’. This has been obscured by their transliteration into English from the Latin ‘spiritus’ as opposed to straight translation. So ‘spirit’ may not be anything in and of itself, but rather a term, acting as a stand in for various functions.

Some confusion has arisen due to Jesus’ personification of the spirit in the later chapters of John, as the ‘paraclete’ who would take over his role subsequent to his ascension. But this is standard Hebraism. One of the best examples would be Solomon’s personification of ‘lady wisdom’ in Proverbs chapter 8. James Dunn’s excellent ‘Christology in the making’ offers many examples from the Judaism of Jesus’ day of the widespread use of this device in relation to God’s attributes.

Even today we would say of a ship, “God bless her and all who sail in her”. But, though we often personalise inanimate objects, we would never refer to a person as an ‘it’ unless we wanted to insult them. Yet throughout both Testaments, God’s spirit is referred to in almost exclusively impersonal terms.

In conclusion, it seems to me that the huge emphasis placed on believing that 'Jesus is God Almighty' by majority Christianity is simply not a reflection of anything found in either Old or New Testaments.

If anything, it has the potential to undermine those things that the Bible does rank as being of first importancem, namely the oneness of Israel's God and the humanity of his unique Son, Jesus.

Have you checked out the main web-site at www.Godfellas.org ?

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

1 comment:

I enjoyed your line of thought and reasoning from the Scriptures. Although the Bible clearly teaches that Jesus had a pre-human existance as Jehovah's first created spirit son, the Scriptures are just as clear that Jesus was, is, and always will be in submission to the heavenly Father and Almighty God, Jehovah.

Post a Comment